A Fight to End the Death Penalty: Stopping the Death Penalty in Taiwan, The Guardian, 3 October 2016

- DPP in the Media

- 3 Oct 2016

As reported by Owen Bowcott, The Guardian, 3 October 2016.

Executions in Taiwan traditionally involve sedated prisoners being thrust face down on a mattress and shot three times through the heart. If the condemned donate their internal organs, death is delivered by a single bullet to the back of the head.

The last execution was at 8.47pm on 10 May inside a jail near the capital, Taipei. Cheng Chieh, 23, received three shots. The crime he committed was a frenzied, mass stabbing of travellers on a metro train, inflicted with a long fruit knife, which left four commuters dead and 24 injured in 2014.

Cheng’s final appeal had been dismissed by the country’s supreme court two and a half weeks earlier. He reportedly confessed: “I had to murder people so I would be convicted for murder and given the death sentence. Only then would my miserable life end.” His mental state was the subject of intense legal dispute.

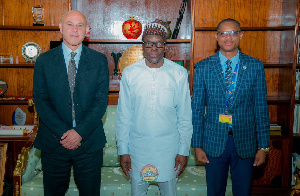

On Tuesday, Keir Starmer, the Labour MP and former director of public prosecutions, the solicitor Saul Lehrfreund, who is co-executive director of abolitionist UK charity the Death Penalty Project, and Dr Richard Latham, a consultant forensic psychiatrist, will arrive in Taipei in the hope of halting further executions.

Their ultimate aim is to persuade the newly elected Democratic Progressive party government of president Tsai Ing-wen that she should abandon capital punishment, a shift that would signal the island’s political distance from mainland China’s practice of executing thousands of prisoners a year.

The problem is that, according to the latest opinion polls, 80% of the Taiwanese population support the death penalty. The challenge does not seem to deter Starmer. “History shows us there are key moments when attitudes change, like the death penalty, or, for example, gay marriage.

The problem is that, according to the latest opinion polls, 80% of the Taiwanese population support the death penalty. The challenge does not seem to deter Starmer. “History shows us there are key moments when attitudes change, like the death penalty, or, for example, gay marriage.

“While popular opinion appears to be strongly in one direction, bold moves are taken in accordance with changing standards. You expect an outpouring of outrage but within a short time a new norm emerges.

“If you said 20 years ago that the public would accept gay marriage, you would have got a very different answer. Rarely has the death penalty been abolished by vote, but it has been restricted by legal measures, then abolished; and that’s been accepted.” Europe, he points out, is now a “death penalty-free zone” with the sole exception of Belarus.

Starmer is a founding director of the Death Penalty Project, and has appeared frequently on a pro bono basis before the privy council – the final court of appeal for many Commonwealth countries – since the 1990s to challenge the use of the death penalty in the Caribbean.

Despite alarm over the recent rate of hangings and beheadings in Saudi Arabia, Iran and Pakistan, the international trend is for countries to abandon executions. There are 109 abolitionist states, although seven retain the punishment for war crimes and treason. A further 39 states abstain in practice.

Taiwan has 42 people on death row. Alongside the US and South Korea, it is one of only a few liberal democracies that supports judicially authorised killing of its citizens. When the present governing party was last in power, it introduced a temporary moratorium and drafted into domestic legislation the United Nation’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prevents the death sentence being imposed on pregnant women or those who committed their crimes below the age of 18.

That moratorium, however, was lifted when the government changed in 2010, leading to the execution of 33 people. The electoral victory this year of Tsai Ing-wen, Taiwan’s first female president, has boosted hopes of converting the country permanently to abolition.

The Democratic Progressive party emerged out of activist opposition to an earlier era of one-party rule. Human rights are part of its core values. The president, who is a lawyer by profession, has so far not committed herself either way.

Lehrfreund says: “We are not there to dictate, we are there to assist them.” He has been working closely with the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty. “We hope Taiwan will show it is respectful of human rights and wants to be different to other countries in the region. That would create momentum for others to switch, perhaps Thailand and South Korea.”

Lehrfreund is convinced that popular support for executions is not set in stone. “Once you throw in variables about innocent defendants being mistakenly executed, then perceptions change.” Challenging “misconceived views about the deterrent effect” of the death penalty also helps shift opinion, he adds.

The experience of awaiting execution can be mentally destabilising, says Latham. “It’s termed ‘death row syndrome’. It has an incredibly negative impact. It resembles a depressive state. Depending on conditions and if you are kept in isolation, prisoners develop more severe responses such as hearing voices and delusional beliefs.” As well as oscillating wildly between hope and fear, inmates overhear neighbours in adjoining cells being dragged away and never coming back.

Latham will be talking to doctors about diagnosing prisoners and the way evidence is handled by the courts. “People can appear superficially to be well but they may nonetheless be mentally disordered.”

Starmer is gratified that what began in obscure privy council legal hearings, has developed into Commonwealth legislation and now broadened out into an international campaign affecting every state around the world.

“It’s for the government in Taiwan to decide whether it wants to move towards abolition,” says Starmer, “but the fact that it has signed up to the ICCPR shows that it wants to do so in accordance with international standards. And that’s welcome.” There will also be discussions about Taiwan’s plans to introduce a jury system.

Progress towards global abolition may not be straightforward, Lehrfreund concedes. Both Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte and Turkey president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threatened this summer to restore the death penalty, setbacks that may overshadow International World Day Against the Death Penalty on 10 October.

“There should be a burden on any state to make sure they are not executing people who are mentally disordered,” Lehrfreund says. “It’s in the political arena that abolition will eventually happen.”