Singapore should be ashamed of lashings

- News

- 3 Sep 2020

Originally published in The Times, 3 September 2020

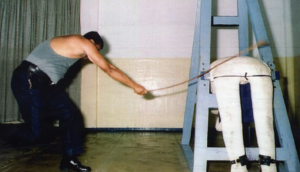

Yuen was strapped naked to a frame and thrashed. He was just one among hundreds of offenders whipped every year in Singapore. There are no official statistics, but the latest estimate is that its government carried out 1,200 floggings in 2016.

By contrast, whipping for criminal offences was abolished in Britain in 1948. Unsurprisingly, the UK has condemned Yuen’s punishment in the strongest terms. The European Court of Human Rights has said that corporal punishment is inherently degrading.

Caning has been found to be a form of inhuman treatment that breaches the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It is also, arguably, a violation of the UN Convention Against Torture.

But none of this seems to matter to the authorities in Singapore. Over the years, the number of criminal offences in the city-state that incur caning has swelled to more than 35. Numbers of strokes have escalated while its government legislates for increasingly harsh sentences.

This is despite any conclusive evidence that caning acts as an effective deterrent. It is not even as though caning is imposed in lieu of another penalty – offenders on the receiving end of corporal punishment are still expected to serve out lengthy prison sentences; Yuen was handed a 20-year term.

This is a state where the courts have found that cruel or inhuman punishments are permissible and have rationalised that its own laws trump any universal norms or international values.

Singapore’s government, parliament and courts have all vigorously defended the ability deliberately to inflict intense physical suffering on offenders, even for what in other jurisdictions might be considered relatively minor offences.

For example, bill posting attracts a minimum of three lashes. Foreigners overstaying their visas are liable to the same number. Some offences that result in corporal punishment in Singapore might not even be regarded as crimes in the UK.

Drug addicts, like Yuen, are treated punitively. Repeat users can be sentenced to up to 13 years imprisonment with a minimum of six strokes if consumption is detected.

Although Singapore boasts of being one of the safest places in the world to live, it comes at considerable cost to human dignity. In the UK, even the staunchest supporter of tougher sentences is likely to balk at flogging.

Harsh sentences are one thing, but outright brutality is quite another. Singapore’s approach to crime and punishment can never be considered successful until it abides by international standards.

The right to freedom from torture and inhuman treatment is a fundamental one and a value that no civilised state should ignore.

Notes to editors

With Edward Fitzgerald QC, The Death Penalty Project provided free legal assistance to Yuen Ye Ming and his local lawyers in Singapore.

The Death Penalty Project is a charity based at the London law firm Simons Murihead & Burton LLP.