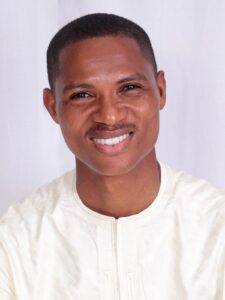

DPP INTERVIEW: Francis-Xavier Sosu, the Ghanaian MP whose private member’s Bills have abolished the death penalty in Ghana

- News

- 28 Jul 2023

This week, Ghana’s Parliament abolished capital punishment for all ordinary crimes by passing two private member’s Bills covering its civilian and military courts, which were introduced by the human rights lawyer and MP for Madina Constituency, Francis-Xavier Sosu. This followed years of engagement with the country’s policymakers and civil society by the London-based NGO, The Death Penalty Project. We interviewed Francis to discuss the background to and his role in this historic event:

It’s been three decades since Ghana carried out an execution. Why has it finally abolished the death penalty in law, as well as in practice?

Ghana may not have carried out an execution for 30 years, but until today, it retained the death penalty as a mandatory sentence for murder, genocide and treason, leaving its judges no choice but to continue to hand down death sentences – there were seven last year. As of the end of 2022, there were 176 death row inmates, a number that was growing every year. However, there has long been evidence that Ghana might be ready to abolish the death penalty. Way back in January 1992, the government announced that all prisoners who had been on death row for more than ten years would have their sentences commuted to life imprisonment, and in 2010, Ghana’s Constitutional Review Commission recommended that the country should abolish the death penalty altogether. The government tried to do this in 2012, but the path it chose, amending the constitution, was problematic, and in the end, it failed. Some of our judges, civil society organisations and human rights activists continued to support this reform, but the movement lacked a spearhead with the ability to make it happen. I was sworn in as an MP in January 2021, and for me, once I had been given this chance, trying to abolish the death penalty was an overriding priority. I came into politics because I wanted to be an agent of change, and this was the change I wanted to achieve most of all. I sensed I was pushing at an open door. The Speaker of Parliament was keen to support abolition, and I knew many of my fellow MPs also believed that capital punishment ought to be done away with. The consensus that Ghana was ready to join the majority of nations – we are the 124th in the world – that have enacted abolition had been building for a long time. I feel blessed and privileged to have been able to help us take the final, legislative steps.

Describe a day in the life of a person sentenced to death in Ghana before capital punishment was abolished.

On death row, prisoners woke up thinking this could be their last day on earth. They were like the living dead: psychologically, they had ceased to be humans. Overcrowding was endemic: a space meant for about 23 inmates could host over 150 prisoners. Most mornings the inmates would sing religious or gospel songs, a ritual that helped them cope with the fear that this was the day that would mark the end of their lives. They were then made to perform various tasks in deplorable conditions, and served with meals which most of us would find inedible. They were isolated from their loved ones, and convinced that even if they were not executed, they would die in prison. I would say that overall, their lives amounted to torture. Condemned cells had poor sanitary facilities and they lacked adequate access to medical care. Many died from avoidable and treatable illnesses before their death sentences were commuted.

Were there other factors that inspired you to sponsor the private members’ bills calling for abolition? Please describe them.

The death penalty is cruel and dehumanizing. Long before I became an MP, I had become aware of miscarriages of justice, in which flaws in our criminal process had led to innocent individuals being sentenced to death. Our police and our courts are hampered by a lack of resources, and this can produce poor quality investigations and unfair trials – a flawed system that led me to write a book with the title Guilty Until Proven Innocent. In my view, it is always wrong for the state to take human life, but when the legal system is imperfect and arbitrary, to allow the death penalty to exist in law is truly pernicious. Of course, Ghana was an abolitionist de facto nation, which the UN defines as a country that has not executed the death penalty for a decade or more, but while capital punishment remains on the statute book, there is always a risk that executions could resume: we saw this in the case of Myanmar last year, where executions have re-started after a moratorium of almost 40 years. Furthermore, despite the claims of its advocates, I have seen first–hand that the death penalty does not bring a sense of justice or closure to the families of crime victims, and neither does it deter offenders. I have also seen that those sentenced to death tend be to vulnerable individuals from deprived backgrounds, who have often experienced deep personal trauma. It was my view that we as a nation were better than this. I introduced these Bills because I wanted the courts to cease imposing an inhuman punishment. Ultimately, I was convinced that the death penalty was alien to the Ghanaian psyche, which places a very high value on the right to life. It had to be expunged.

What challenges have you had to overcome to drive abolition legislation forward?

It has not been an easy journey. The concept of the private member’s Bill is relatively new in Ghana, and so the Bills’ supporters and I were negotiating unfamiliar territory as we tried to guide them through Parliament. At the same time, I was a new, backbench MP, and at first, I experienced some pushback from senior figures and people who had been in Parliament for many years. I think some of them felt this was too substantial and weighty an issue to be raised by a junior private member. The second of the Bills, which deals with the military courts, amends Ghana’s Armed Forces Act. I will always remember the day that a five-term senior MP rose in the House and said this Bill could not proceed without prior engagement and consultation with Ghana’s military leadership in case it had an impact on national security! Thankfully, those concerns had already been addressed at a consultative meeting at which Ghana’s Armed Forces had given their approval.

Some members openly told me they were against my bills, including the Attorney-General and the first Deputy Speaker. For me as a backbencher, that felt like a major setback, but I was determined to continue to build consensus and get majority support. I tested this by making a statement on the floor of Parliament. Others then made contributions. Six MPs spoke in favour of abolition and two spoke against, claiming the Bills would breach Ghana’s constitution. Indeed, on the day the Bills were first presented last year some MPs attempted to block their progress by “arresting” them, but they were overruled by the Speaker, who ordered that the Bills be referred and considered by the Constitutional, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee.

Another hurdle I had to face was that by launching the Bills I had basically assumed financial responsibility for ensuring their passage. We needed to hold events with civil society organisations and others to ensure we had the widest possible base of support – and getting this together took time and money.

Once the Bills had been introduced, I had to seek support from colleagues from both sides of the House, and especially those on the Constitutional, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee, where I serve as deputy Ranking Member. The committee’s job was to undertake a clause by clause consideration of the Bills, and then issue a report rejecting or recommending them. This meant I had to engage thoroughly with all its members to obtain their commitment and support. This was a major challenge, that required tact and consistent lobbying – not only to persuade colleagues to support the case for abolition, but on more basic matters too, such as getting suitable dates for the committee to conduct its reviews. There were also numerous meetings with the committee, political leaders, and national and international bodies such as such as Amnesty International Ghana, The Death Penalty Project, and other Institutions with interest in abolition.

The final stage was to guide the Bills through Parliament. Over the months I made statements on the floor of the House and asked relevant parliamentary questions to appropriate ministers to keep the subject on the parliamentary burner. Each time the subject was raised I took pains to gauge potential support as well as threats to the passage of the Bills. This went a long way towards building the necessary majority, because I did what I could to target MPs who needed to be further engaged or approached.

What does it mean for Ghana to eradicate capital punishment from law?

I believe that the world over, justice systems are far from perfect, and Ghana is no exception. But we are among the signatories to treaties and conventions including the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. By abolishing the death penalty, we have joined a global community that reflects the values these documents embody by doing away with the death penalty. In that sense, the passage of the Bills feels as if Ghana has come of age.

We have also joined a swelling movement of which I proud in our African sibling nations. Other African countries that have abolished capital punishment include Rwanda, Burundi, Togo, Gabon, Congo, Madagascar, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Chad, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe, Zambia, Sierra Leone, Angola, Guinea Bissau, Papua New Guinea, Djibouti, Mauritius, South Africa, Cote D’Ivoire, Senegal, Liberia, and Kenya. The time had come for Ghana to chart a similar path, given our democratic and human rights credentials, and to affirm the statement by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres that the death penalty has no place in the 21st Century.

In all, some 124 countries have so far abolished the death penalty, so by taking this step we have also aligned ourselves with a global trend. More are added to the list every year.

The former UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon, once said: “The taking of life is too absolute, too irreversible, for one human being to inflict it on another, even when backed by legal process.” Abolishing the death penalty shows that we are determined as a society not to be inhumane, uncivil, closed, retrogressive and dark. It opens the way to further realization of a free, open, progressive, inclusive and secure society instead, and reflects our common belief that the sanctity of life is inviolable.

How has The Death Penalty Project supported your efforts towards abolition over the past year?

Since well before I became an MP and presented these Bills to Parliament, the Death Penalty Project has provided immerse technical support and assistance to all those seeking an end to capital punishment. In the past two years it has gave us timely research, helped our engagement with stakeholders, and in general was an enormous help in suggesting what might be the best way to reach our goal. Its inputs and research provided much needed intellectual ammunition, allowing us to hone our arguments against those who supported retention of the death penalty in Ghana.

The Death Penalty Project also provided vital financial support, and actively took part in the various processes necessary that had to be completed to ensure successful passage of the Bills. All through this, we found The Death Penalty Project to be a reliable and trustworthy partner.

What added value has The Death Penalty Project (and the experts we have engaged) been able to bring to the conversation?

The Death Penalty Project made our advocacy richer, allowing us to explore different dimensions in our advocacy, particularly with opinion survey research, which was key in challenging popular perceptions about Ghana’s mandatory death penalty. The Death Penalty Project and the experts it brought to Ghana met leading figures who played significant roles. They included officials at the Attorney-General’s department, Ghana’s parliamentary leadership, religious leaders, Civil Society Organisations, the Ghana Bar Association, members of the judiciary and of the Constitutional, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Committee, the Speaker, and many key MPs. While local efforts had made some progress, thanks to the advocacy and work of Amnesty International Ghana, the Death Penalty Project was able to accelerate and enhance it. Their thorough, meticulous research, constant engagement, tenacity and financial support was of incalculable value in garnering majority support for the legal abolition of the death penalty in Ghana.

Francis-Xavier Sosu on why he called for abolition:

I have seen first–hand that the death penalty does not bring a sense of justice or closure to the families of crime victims, and neither does it deter offenders. I have also seen that those sentenced to death tend be to vulnerable individuals from deprived backgrounds, who have often experienced deep personal trauma. It was my view that we as a nation were better than this. I introduced these Bills because I wanted the courts to cease imposing an inhuman punishment. Ultimately, I was convinced that the death penalty was alien to the Ghanaian psyche, which places a very high value on the right to life. It had to be expunged.