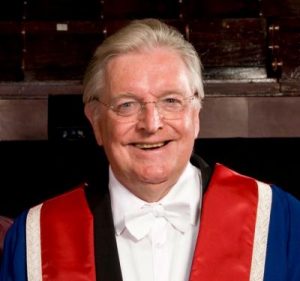

Professor Roger Hood obituary

- News

- 9 Dec 2020

Originally published in The Times, 9 December 2020

Criminologist who made a career studying the death penalty and whose research was instrumental in the abolitionist campaign

Roger Hood began his criminology career by studying sentencing in magistrates’ courts. Like a true recidivist he wound his way through the criminal justice system, taking in borstals and motoring offences, until emerging as a leading authority on the death penalty.

Hood was adamant that judicial execution, which was abolished in Britain in 1965, posed little or no deterrent. It was a view confirmed by his research on murders committed in Trinidad and Tobago around the turn of the century for the Death Penalty Project, a London-based charity, which indicated that the mandatory death sentence not only failed to deter violent crime, but made it worse. He pointed out that most Americans who favour the death penalty do so because they think the criminal deserved it, not because they see it as a deterrent.

In the late 1980s the UN commissioned Hood to research the extent to which capital punishment was still used in member states. His report formed the basis of his book The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective (1989), which remains one of the best-known pieces of literature on the subject. He repeated the UN exercise on several occasions and a fifth edition of his book was published by OUP in 2015.

In 2001 Robin Cook, the foreign secretary, invited Hood to join a panel on abolition, taking the British government’s abolitionist message to countries that still have the death penalty, including China, India and Malaysia. According to the Death Penalty Project, 75 per cent of countries are today abolitionist in either law or practice.

Many years earlier, his book Sentencing in Magistrates Courts (1962) had contributed to a move to provide JPs with better training after Hood revealed sentencing disparity from a dozen magistrates courts, suggesting that the different approaches appeared to stem from different bench traditions.

One of Hood’s great concerns was the impact of a defendant’s race and social background on sentencing. In Race and Sentencing (1992) he looked at more than 3,000 cases in five crown courts in the West Midlands and found that people of colour had a 5 per cent greater probability of receiving a custodial sentence compared with their white counterparts.

Hood was concerned that too many of his criminology students at the University of Oxford lacked first-hand experience of the criminal justice system. He addressed that by taking them to meet residents of Oxford prison, lubricating their get-togethers with gifts of cigarettes and chocolate. “They would hear of prisoners’ attitudes to imprisonment and probation, and what could affect their return into society,” he told The Oxford Times in 2012, by which time the prison had been converted into a hotel. To break the ice he would ask inmates: “Most people assume prison is a deterrent, so how come that it was not a deterrent for you?”

Roger Grahame Hood was born in Bristol in 1936, the second of three sons of Ronald Hood, and his wife Phyllis (née Murphy). The family moved to Birmingham, where Phyllis worked in ladieswear at Rackhams department store and Ronald became a stockbroker’s dealer before spending the war with the Royal Artillery while the family lived with relatives in Leeds.

Returning to Birmingham, Hood was educated at King Edward’s School and won a scholarship to read sociology at the London School of Economics. Hood attended an optional course there given by Hermann Mannheim, the “grand old man” of criminology, who asked for help preparing a paper about the Homicide Bill, which eliminated the death penalty for so-called crimes of passion and became law in 1957. “Mannheim was so pleased with it that he asked me if I would be his research assistant,” Hood recalled.

He returned to the LSE as a research officer in 1961 and was “given a very large grant to try to improve methods of research in criminology”. In 1963, the same year as he was appointed lecturer at the University of Durham, he married Barbara Young, a housing adviser. They had a daughter, Cathy, who produces TV commercials and who survives him. The marriage was dissolved and in 1985 he married Nancy Stebbing (née Lynah), who died last year. She worked for Oxfordshire museum service and wrote books on local history.

In 1967 Hood joined the Institute of Criminology at the University of Cambridge, with a fellowship at Clare Hall. Six years later he became founding director of the Centre for Criminology at the University of Oxford with a fellowship at All Souls College, where his love of cooking spilled over into helping to select the fellows’ menus.

At home his signature dish was dover sole with a vermouth sauce and oven-baked fennel, washed down by a glass of wine. A 6pm Martini was de rigueur. He collected ceramics and enjoyed walking by the river, with stick to hand and wearing a fedora, chatting sociably to whoever passed by. In his study was a collection of old prints depicting grizzly methods of execution.

After retiring in 2003 Hood became ever more engaged in abolition work with the Death Penalty Project, especially in the US, China, Japan, the Caribbean and Africa. He remained optimistic that capital punishment would eventually be eliminated.

Professor Roger Hood, CBE, criminologist, was born on June 12, 1936. He died of pneumonia on November 17, 2020, aged 84